Prevention of Exertional Heat-Related Illnesses

by: Melinda Flegel©

More from this issue

The key to prevention is balancing all the factors that influence body temperature so that the body temperature stays within a safe range. Here’s how:

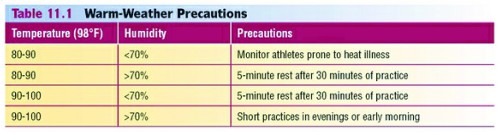

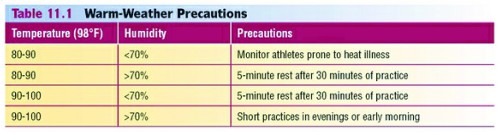

Monitor weather conditions and adjust practices accordingly. Table 11.1 shows the specific air temperature and humidity percentages that can be hazardous. Keep in mind, however that football exertional heat-related deaths have occurred at temperatures as low as 82 degrees with a relative humidity index at only 40 percent. If heat and humidity are equal to or higher than these conditions, make sure athletes are acclimated to the weather and are wearing light practice clothing. Schedule practices for early morning and evening to avoid the heat of the day.

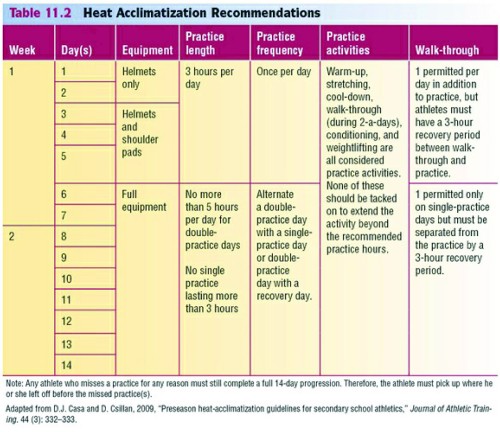

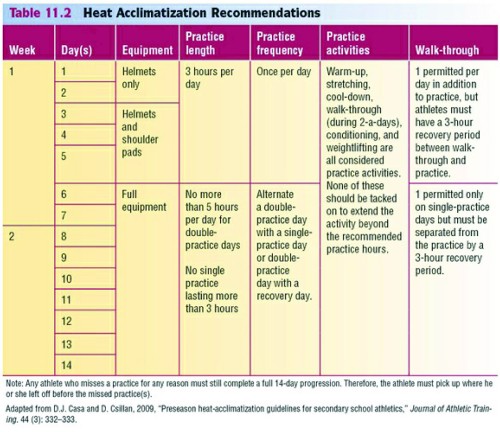

Acclimate athletes to exercising in high heat and humidity. If you are located in a warm-weather climate or have practices during the summer, athletes need time (approximately 7 to 10 days) to adjust to high heat and humidity. During this time, hold short practices at low to moderate activity levels and provide fluid and rest breaks every 15 to 20 minutes. The National Athletic Trainers’ Association 2009 Consensus Statement offers more specific guidelines for acclimating high school athletes to hot environmental conditions. Table 11.2 summarizes the organization’s recommendations.

Switch to light clothing and less equipment. Athletes stay cooler if they wear shorts, white T-shirts, and less equipment (especially helmets and pads). Equipment blocks the ability of sweat to evaporate. It’s especially important for athletes to wear light clothing and minimal equipment while they are acclimating to the heat.

Identify and monitor athletes who are prone to heat illness. Athletes who have previously suffered a heat illness and those with the sickle cell trait are particularly prone to exertional heat illness and should be continuously monitored during activity. Dehydrated, overweight, heavily muscled, or deconditioned athletes are at risk, as well as athletes taking certain medications (antihistamines, decongestants, some asthma medications, certain supplements, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications). Closely monitor these athletes and make sure they drink plenty of fluids. Rest dehydrated athletes until they have become rehydrated.

The signs and symptoms of dehydration include:

• Thirst

• Flushed skin

• Fatigue

• Muscle cramps

• Apathy

• Dry lips and mouth

• Dark colored urine (should be clear or light yellow)

• Feeling weak.

Strictly enforce adequate hydration. Athletes can lose a great deal of water through sweat. If this fluid is not replaced, the body will have less water to cool itself and will become dehydrated. Dehydration not only increases athletes’ risk for heat illness, it also decreases their performance. In fact, athletic performance may worsen after only 2 percent of the body weight is lost through sweat. For example, dehydrated athletes may experience:

• Decreased muscle strength

• Increased fatigue

• Decreased mental function

(e.g., concentration)

• Decreased endurance.

Don’t rely on athletes to drink enough fluids on their own. Most won’t actually feel thirsty until they’ve lost 3 percent or more of their body weight in sweat (water). By that time their performance will have started to decrease and their risk of exertional heat illness will have increased. Also, they may not drink enough fluid to replenish the water lost through sweat.

• For proper hydration, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association recommends:

• 17 to 20 fluid ounces of fluid at least 2 hours before workouts, practice, or competition.

• Another 7 to 10 fluid ounces of water or sports drink 10 to 15 minutes before workouts, practice, or competition.

• As a general guideline, 7 to 10 fluid ounces of cool (50 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit) water or sports drink every 10 to 20 minutes during workouts, practice, or competition.

• After workouts, practices, and competitions, 24 fluid ounces of water or sports drink for every pound of fluid lost through sweat.

• To determine the amount of weight lost through sweat, weigh athletes in their underwear before and after practices and competitions that take place in high heat and humidity.

Replenish electrolytes lost through sweat. During activities lasting longer than 45 to 50 minutes, substantial amounts of electrolytes such as sodium (salt) and potassium are lost in sweat. They are used in muscle contraction, fluid balance, and other body functions, and therefore must be replaced. In addition, sodium plays a role in activating the body’s thirst mechanism, so it can stimulate athletes to drink (keep hydrated). The best way for athletes to replace these nutrients is by drinking a sports beverage (containing sodium) and eating a normal diet. Athletes can also replace sodium by lightly salting their food, so salt tablets are not recommended. Just a small amount of potassium is lost in sweat. Oranges and bananas are good sources of potassium.

Prohibit the use of sweatboxes, vinyl suits, diuretics, or other artificial means of quick weight reduction. The NFHS Wrestling Rules Committee has already prohibited these methods.

Identifying and Treating

Exertional Heat Illnesses

During physical activity, the body can produce 10 to 20 times the amount of heat that it produces at rest (metabolism). Approximately 75 percent of this heat must be eliminated. If the air temperature is less than the body temperature, radiation, conduction, and convection can help dissipate 65 to 75 percent of this heat. However, if the air temperature is near the body temperature, these modes of heat loss are less effective, and the body has to rely more on perspiration. High humidity reduces the amount of sweat evaporation, and thus leaves exercising athletes at risk of exertional heat illness.

There are three types of exertional heat illness:

• Heat cramps

• Heat exhaustion

• Heatstroke

Each has different signs and symptoms, as well as different first aid interventions. Heatstroke is life threatening, whereas heat exhaustion and heat cramps typically are not. Therefore, it is important that you learn to evaluate the signs and symptoms and learn to apply the first aid techniques that are appropriate for each illness. p

Editor’s Note: The preceding is an excerpt from Sport First Aid, Fifth Edition (Human Kinetics, 2013), written by Melinda Flegel. Sport First Aid is the textbook for the Sport First Aid course, available through the Human Kinetics Coach Education Program and used by the majority of state high school associations, athletic directors associations, and school districts for certifying high school coaches. The Sport First Aid text and course are available at www.HumanKineticsCoachEducationCenter.com. (All content provided by Human Kinetics).