Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

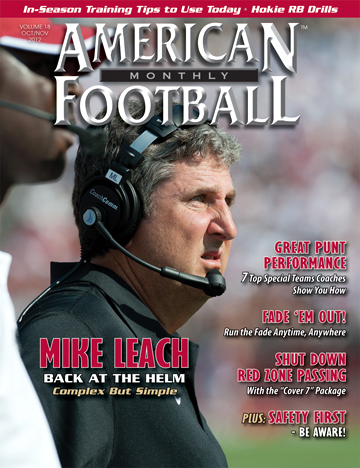

The Pirate Returns - Mike Leach brings his high-powered but surprisingly simple passing offense to Washington Stateby: David Purdum© More from this issue Mike Leach is complex. Contrary to popular belief, his coaching philosophy is not. Dating back to his early days as an innovative offensive coordinator at Iowa Wesleyan and Valdosta State, Leach has always experimented with unique plays and unusual ideas. Yet, two decades later, his first offense at Washington State has just 14 pass plays.

“And a bunch of screens,” Leach pointed out during a summer phone interview. It’s not that he has resisted adding new plays to his scheme. He’s tweaked plenty during his 25-year coaching career. But when he adds a new wrinkle, he eliminates something else. He prefers to keep his scheme lean, rather than complicated. “I think anything that causes hesitation among the players is a negative thing. And it’s going to hurt you. It’s going to slow you down,” Leach emphasized. “You can have the smartest things in the world on the board, but if it’s too much and the players can’t execute it without hesitating, then you are going to hurt yourself.” Leach arrived at Washington State with an 84-43 record as a head coach, all at Texas Tech. Prior to the start of fall practice, he broke his Air Raid scheme into pieces and implemented a certain amount every day, always making sure to focus on the detailed execution of the plays. In August, he spent an entire practice period perfecting one play. “The rarest commodity you have is reps,” Leach explained. “If you use up all the reps on trying to put in new things, then you don’t have the reps left to develop the skills and plays that are the core of your scheme. “Too often coaches see something that everybody down the road is doing and they try to add it,” he added. “It gets to a point where they can’t efficiently practice what they already do. I also think it’s important to make your choices [on plays] so that when you go out there and practice you can focus all your effort on execution, because this is still, most importantly, a game of execution. I think sometimes you can get caught up in strength, skills and fundamentals, when the most important thing remains execution.”

“Most coaches make the mistake of over-coaching, over-planning, having too much in and trying to outwork everyone. Mike is different,” said Foothill (CA) High School coach Bryon Hamilton, who knows Leach personally and professionally. “He wants to out-efficient everyone and he usually does. He lets the opposing coaches worry about stopping everything while he works on staying simple and beating you with precision and intelligence.” New Washington State inside Receivers Coach Eric Morris agrees. “He’s really good at finding out what we’re good at as a team,” said Morris, who also played wide receiver for Leach at Texas Tech. “There are a lot of offensive coordinators who are always looking to add a wrinkle here or a wrinkle there, but that’s not him. He’s always trying to get rid of as many plays as he can and run the ones that were good more often.” In addition to simplifying his system instead of complicating it, Leach takes a different approach to time management than many coaches. “He is not one of those coaches who comes in at 5am and leaves at midnight,” according to Hamilton. “He gets in, gets out, and gets it done. I have noticed that with Mike, time is not an issue. If something takes five minutes, then he will take five minutes and move on. If it takes five hours, then he will work for five hours and move on. This is a refreshing approach with today’s ‘grinders’ mentality that most high school and college coaches have.” “Bear in mind, most of my quarterbacks have spent time in the NFL,” he quickly responded, in his deep voice with tempered frustration. Nevertheless, he’s glad his offense has a clear-cut identity. When recruiting, it allows him to pinpoint quarterbacks with the skill set – accuracy and good decision-making – required to have success in the Air Raid offense. Leach spends a lot of one-of-one time with his quarterbacks. He says that’s just part of the deal of playing for him. In the film room, he teaches things like where he wants the QB’s eyes to be on certain plays and when to look at a certain area of the field. On the practice field, he reinforces the lessons with repetitions of route configurations against a variety of defenses. “ Do it over and over so he really learns the dimension of the play and the various situations,” Leach advised. “You want him to have seen as many looks as he can.” Most importantly, Leach wants his quarterbacks to be confident. He wants them to never hesitate. “Confidence is a huge commodity for a quarterback. It’s the most important characteristic,” Leach said. “If you blast their confidence too much, they are going to go to the tank and are not going to come out.” When deciding when and in front of whom to criticize his quarterback, Leach picks his spots carefully. He not only wants the quarterback to be confident, but he also wants the team to have confidence in him. “If you are going to get on the whole group, then you start with the quarterback,” he said. “But if you are going to just put it on your quarterback, then you do that in more of a one-on-one situation. Part of that is because you are telling your team to believe in the QB and respond to the quarterback. And if you destroy his credibility in front of the group then their mentality is, ‘if you don’t believe in him, then why should we?’ You always have to reinforce that. If he’s in charge in a scrimmage and he makes the wrong choice and makes a mistake, I don’t think that you can just verbally blow him up. You can make him gun shy. If he is trying hard, I always try to build him up.” Bryon Hamilton was at Washington State recently assisting in a camp with Leach and his staff. “I talked to all of his assistants while I was there and they all said that working with Mike was much different than working at the other places that they have been,” said Hamilton. “They said that he doesn’t worry about the peripheral things and only spends his time on the ‘meat and potatoes’. He runs practice differently, recruits differently, plans differently, calls plays differently, and has a different philosophy than almost any other coach. That, to me, is what makes Mike so intriguing and what coaches should pay attention to. These philosophies can be applied and studied by every coach regardless of what offense they run.” In reality, Leach has been successful because his approach allows players to execute at a higher level, with no hesitation, much like the way he coaches and lives his life. “Everyone looks at him like he has some magic formula,” said Bruce Feldman, who worked with Leach on his autobiography, “when really it all boils down to simplicity.”

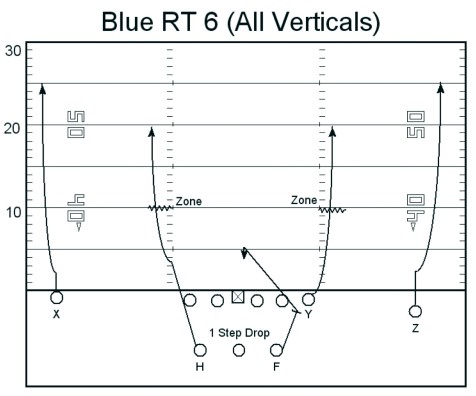

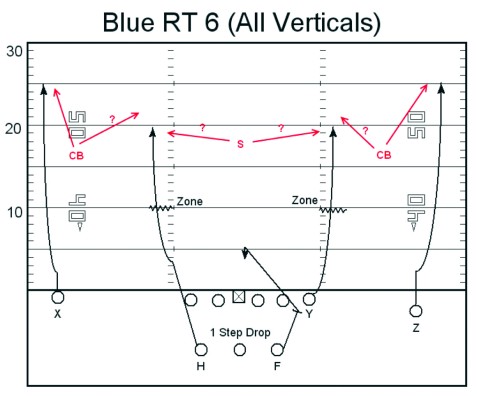

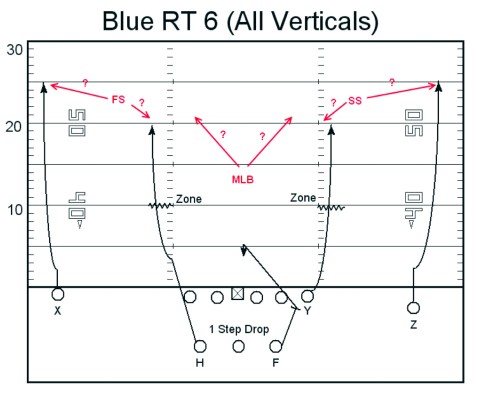

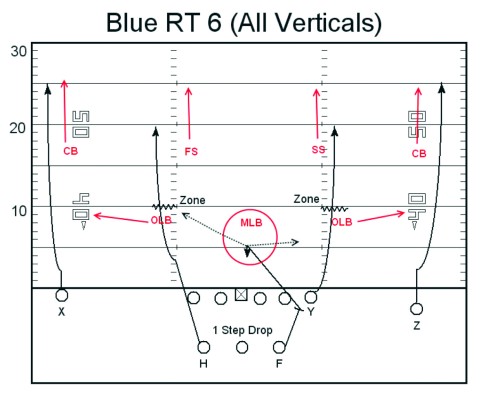

The Ultimate Four Verticals Play: ‘6’

There is nothing simpler in the whole world of football than 4-Verticals, or “6.” Since the game of football was invented, since the days of the cavemen, they ran this play. Back then it was called “Everybody Go Deep.” At Tech we’d run it a bit differently than most teams did. We’d settle our receivers down and throw it behind them. When the DB turned and flipped his hips, our receiver would look back to the quarterback, but he still ran fast. We coached our receivers to “let the ball take you to the play.” Our guys looked for the ball often, and we wanted them to. We drilled it over and over and over again to hit it at all points along the way. You could stick great defensive backs at every position in the defensive secondary and they would have a difficult time stopping it. Now, a great DB might be able to narrow your margin for error, but he couldn’t stop it. Of course, the tricky part is that the quarterback and the wide receiver have to be on the same page. It has to be precisely executed or else you end up stopping it yourself. The upside is that our QB could hit his receiver at any point, starting from right on the line of scrimmage all the way to 35 yards downfield. Somewhere along that path he’s bound to be open. And that’s just one guy. Multiply that by four. Then, for good measure, we’d stick a back underneath and release him right or left or through the line by the center and tell him to “Get open!” after we’d blown the top of their coverage. It’s a beautiful thing to see all that space open up for a back. The downside is that “6” becomes a game of execution and anticipation. The quarterback and his receivers have to be on the same page as those windows come open. It has to be in the quarterback’s head, “He’s about to hit a window, I have to throw this thing right now.” At Tech, we were big on looking at the quarterback. People say, “Well, that’s going to slow you down.” Well, not very much. Michael Crabtree, who caught 134 passes for 1,962 yards and 22 touchdowns in his freshman season at Tech, was always looking at the QB, and he would never quit working on a play. He might be the fifth read, but without breaking the integrity of the play, he’d keep working, keep working, keep working – and we’re talking about a guy that was a ridiculously marked player – but he’d still make a ton of mop-up plays because he kept hustling. A turning point for us came in my third season at Tech, which was also Kliff Kingsbury’s third year as our starting quarterback. We got to thinking about all of this space we weren’t utilizing. Why weren’t we using it? I saw all this real estate out there that was just being wasted. Run or pass, it’s a constant effort to best utilize the space on the field. We told our players to work on verticals all off-season, but when we came back they clearly hadn’t worked on them that much. So in the first couple of days of camp, we decided to throw verticals all the time. The first day we completed about 30 percent, and I said, “That’s bad. We need to do a better job of getting on the same page and this is something we really need to look at.” So we talked about it. “If he’s open here, you need to throw it. If he’s open now, you need to look. You guys aren’t on the same page, but we need to get on the same page because there’s space everywhere.” I love the curl route, but even if you have great technique you can only be open at the tail end of the route. The corner route is the same way. With vertical routes, there are a lot of chances to be open between the point where you start and 35 yards downfield. There’s going to be a learning curve with a vertical route that’s more severe than there is with a horizontal route, like a dig route or a curl route. The receiver runs the route and looks to the quarterback as the defender adjusts. The receiver keeps running. The quarterback decides when and where to throw the ball. On the throw, the receiver adjusts to the ball. If the receiver stops or settles because he guesses, then he is wrong. If the ball is thrown to the wrong place, where there is no space, then the quarterback is wrong. Where the ball is caught is based upon how the defender chooses to play the route. Simply stated: Throw it where they In Kliff’s first two seasons as a starter, he averaged 23 TD passes and around 3,450 passing yards. His third season, after we changed our approach on “6,” he threw for 41 TDs and 4,500 passing yards. Copyright ©2011. Reprinted with permission from Diversion Books. |

|

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2025, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved

Leach’s passion for pirates and out-of-the-box thinking has drawn analogies to a mad scientist, but in reality, coaches who have worked with him say he’s much more of an efficiency doctor.

Leach’s passion for pirates and out-of-the-box thinking has drawn analogies to a mad scientist, but in reality, coaches who have worked with him say he’s much more of an efficiency doctor.

Washington State coach Mike Leach runs a simple four verticals pass he calls ‘6.’ In his autobography written with Bruce Feldman, ‘Swing Your Sword - Leading the Charge in Football and Life’ - Leach explains the strategy for this play.

Washington State coach Mike Leach runs a simple four verticals pass he calls ‘6.’ In his autobography written with Bruce Feldman, ‘Swing Your Sword - Leading the Charge in Football and Life’ - Leach explains the strategy for this play.