Article CategoriesAFM Magazine

|

The Fix Is In – Adjusting your defense at halftime and during the game can pay big dividends.by: Curt Block© More from this issue All coaches know that tweaking a defensive scheme during a game or at halftime can often make the difference between winning and losing. But how do some of the game’s best defensive minds approach in-game defensive adjustments? Is it better to completely revamp a defensive game plan or is it better to make minor adjustments based on what you’ve seen from an offense? AFM asked three prominent defensive coordinators about their approaches to in-game defensive adjustments and found some specific examples of defensive fixes that helped win games. Al Groh has spent 38 years making defensive adjustments. As the head coach of the Wake Forest Demon Deacons, the New York Jets and the Virginia Cavaliers, his teams were known as defense-first squads. Now, heading up Georgia Tech’s defensive unit, Groh concentrates on dealing with powerhouse ACC offenses and the wrinkles they add to their game plans every week. Going into a game, Groh knows what to expect from an opposing offense. “We know things we have on video that they’ve done,” he said. “We’re plotting against those things. How can we take advantage of some of the weaknesses we’ve seen that the other side has? We try to make sure our players are never at a competitive disadvantage. We don’t want them to ever be outnumbered or out-leveraged.” Regardless of the amount of preparation Groh puts into his defensive game planning, there are always situations that occur after kickoff that require adjustments in formation, tactics and personnel. “There’s a constant strategic and tactical competition that goes on throughout the course of a game, so your game planning for an opponent is frequently just a way to start a game,” said Groh. “A great deal of the time, adjustments are necessary and sometimes they have to be high speed adjustments,” said Groh. “You know from your system and your experience that if you have a particular incident happen during a game, that you have a specific way of dealing with it.” Halftime is a chance to review and at the same time the last extended opportunity to speak to the team as a whole. With so much to digest and so many voices with suggestions to offer, a defensive coordinator must utilize his time with the players and his assistant coaches to maximum efficiency. For Groh, halftime is the critical opportunity to analyze what an offense presented in the first half and develop and communicate an adjusted defensive game plan for the second half. “Halftime is an opportunity to get an edge,” he said. “We want to do a better job with halftime than our competition, so you have to have a plan for how it’s going to be done.” That starts with thinking ahead, on the fly, about your specific plan to take advantage of the precious minutes in the locker room. “You’re thinking about halftime while you’re running to the locker room. You know that the clock is ticking. As time is winding down to halftime, I begin organizing in my mind what we’re going to cover. You can’t narrate the whole half, so you have to focus on what’s most important.” Groh and his staff try to determine how the opposing offense will play in the second half based on their success in the first half. “Part of knowing your opponent is knowing if this is a team that has a history of saving something for the second half,” said Groh. “Or is this team a case of what you see is what you get.” Give and take with his players at the break is encouraged. “We want to give the players the picture,” he said. “Hopefully, some things are so ingrained in what we’re doing that we can just highlight them verbally. But we continually are asking the players ‘Does everybody have this? Anybody got a problem with this?’” Honesty is also key for Groh. “We have to be truthful with each other,” he said. “I’m going to ask my player, ‘Hey, Joe, can you handle this guy? If you can’t I can give you some help. But can you handle him on your own?’” At halftime, Groh might also eliminate what his defense doesn’t need for the second half – a specific scheme, blitz or cover – or feature some things even more. Above all, he said, keep the changes as simple as possible. “Tell them which calls we’re going to feature in the second half. Have an extremely short list of some changes you want to make. And those things should be things that the players already have a great deal of familiarity with.” Perhaps the critical element of Groh’s halftime strategy is developing a sense of defensive unity. “The most important thing is to establish a collective mentality on what you need to do to win the game.” Sifrit believes there are six keys he must address at halftime with his other defensive coaches and his players. Changing checks and formations - Dwyer’s defensive staff tells players the different checks that they will use in the second half, which often are completely different than the ones used in the first half. “We’ll also make subtle changes in our defensive alignment in the second half,” said Sifrit. It’s faith in their defensive game plan that gives Reynolds the confidence to make minimal in-game adjustments in the first half. “If something bad happens to us early, it’s usually our fault, so we won’t abandon ship.” Reynolds views halftime not as an opportunity to make wholesale changes, but rather to tweak his defense in preparation for the second half. “We keep our halftime adjustments limited,” he said. He does, however, have a specific halftime routine. “At the start of halftime, our guys in the box will come down. Our defensive staff, along with the guys upstairs, will huddle up with the coaching staff and have a quick 3-5 minute meeting to go over what their tendencies were and go over what’s working well for us in the first half and what isn’t. We bounce some ideas off each other and discuss what we want to do.” The Hamilton staff also uses the white board to show the opponent’s offensive sets and formations and how they will defend them. “We also want to talk about any personnel advantages or disadvantages we may have such as are we quicker on the defensive line than they are, are we bigger and stronger?” said Reynolds. “Do our defensive backs and linebackers match up with their skill players as far as the pass game goes? We show them on the board and talk to them as well. Every halftime is different, depending on the score or who we’re playing.” Reynolds also makes a point of focusing on what went right. “If it’s a rival team or a non-conference team, some factors can come into play but we definitely point out all the good things they did in the first half as well as the things they need to work on,” said Reynolds. “But we won’t jump on a kid and crush his ego. We will, however, point to the areas where we need to get better during the second half. We don’t change anything too much, although we may add a wrinkle here or there or take something out.” Dwyer’s Safety Zone Sifrit and his Dwyer Panthers had to adjust immediately at the start of the state semi-final playoff game against Plant High School three seasons ago. Plant’s outstanding quarterback Aaron Murray was recovering from a broken leg suffered earlier in the season. Sifrit’s game plan was designed to confuse Plant’s less experienced second stringer. “We thought we were okay playing three deep against trips versus the backup,” Sifrit remembers (Diagram 1). This was Dwyer’s alignment.

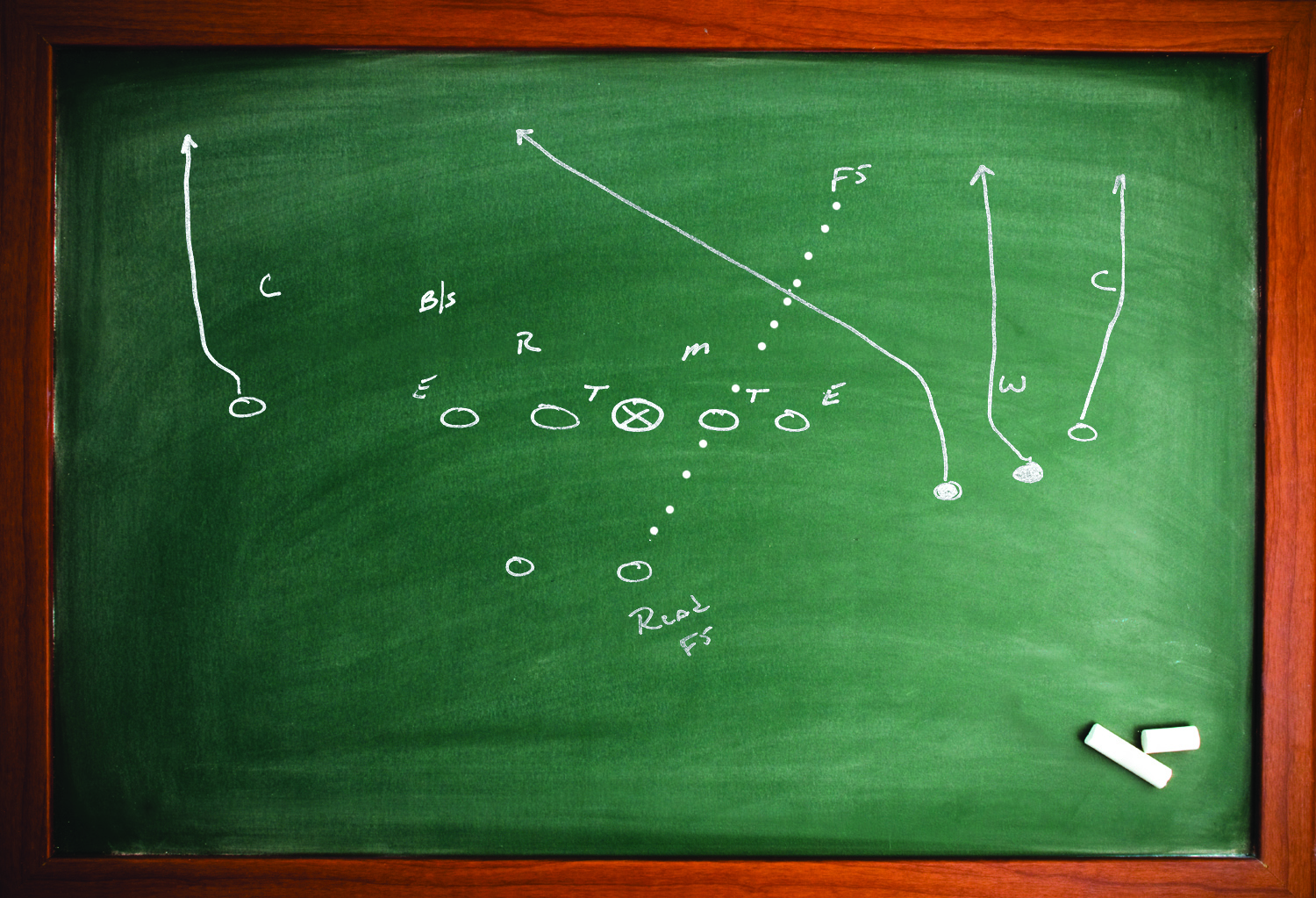

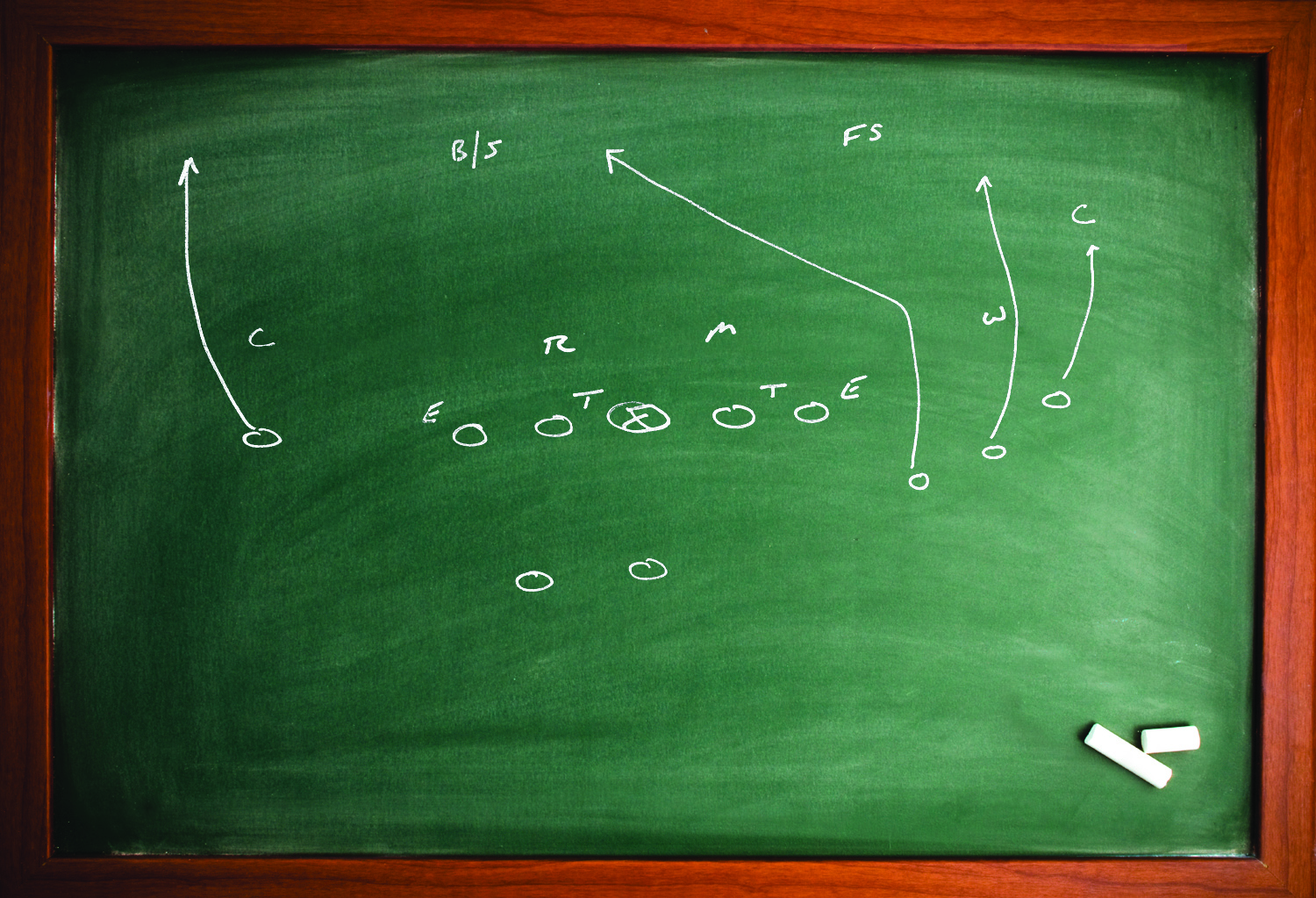

Diagram 1. FS - Free safety What Dwyer was not prepared for was seeing Murray (now the starting QB at Georgia) come onto the field to guide the offense. “Murray came out on the first play of the game and ran a pattern where he read our safety and threw an absolute laser to the second receiver on a trip side up the hash,” said Sifrit. “Our safety drifted to the side when the third receiver crossed his face toward the opposite hash. When Murray completed this throw, all the coaches upstairs looked at each other, realizing that was the last time we could use a single high safety versus trips in that game. His arm was so strong that if we didn’t adjust they might have scored on every series by using it.” So Sifrit adjusted by using a single high safety, taking the boundary safety out of the box and making him a half-field player on the opposite side of the trips formation. “In that formation, we can pick up the third receiver coming across to the hash and let our free safety take the second receiver who is going upfield vertically to the trip side,” said Sifrit. “On the play that burned us, the free safety took two steps with that third receiver giving Murray time to hit the second receiver.” By adjusting the safety to concentrate on the second wide receiver, Dwyer had taken away one of Plant’s most effective options (Diagram 2).

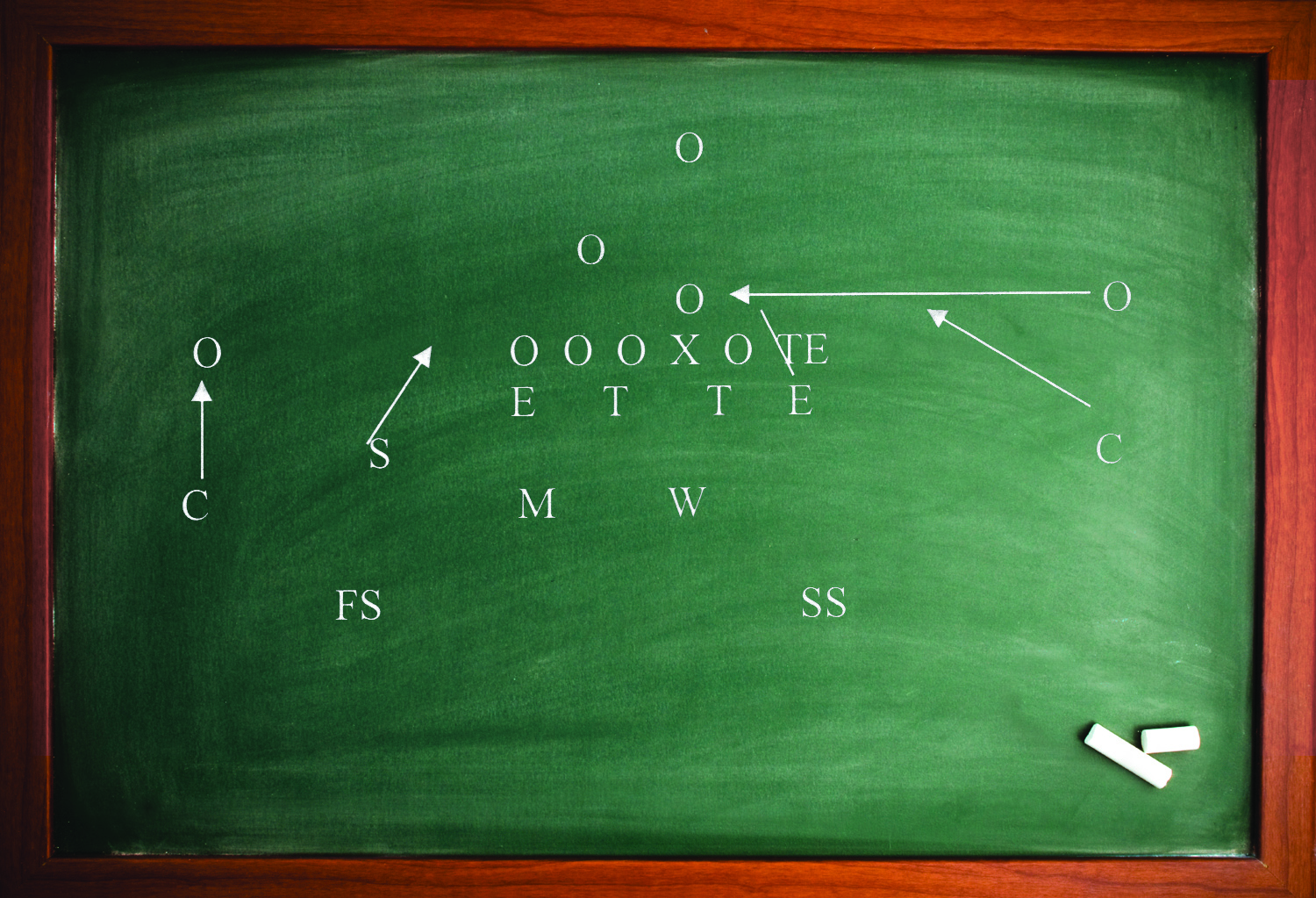

Diagram 2. Hamilton’s Joker’s Wild Lane Reynolds was confronted with a particularly challenging situation this past season. “A rival opponent had been using an unbalanced set frequently,” he said. “They used a ‘tackle over’ set (Diagram 3) with the TE backside. They primarily used this set to put their three best blockers to one side and try to overload the defense. They would motion the backside receiver and their three best run plays out of that formation on a fly sweep, power and lead to the ‘tackle over’ side.”

Diagram 3 Hamilton ran a gap control 4-2-5 defense with a “two high” safety look playing quarters coverage. They entered that game with a “joker” check against their alignment. This meant that when their opponent showed that formation, Hamilton would check ‘joker’ and line up with specific assignments. Hamilton believed their coverage could match up man-to-man against their opponent’s personnel and could take away strengths both in the run game and in the passing game. The game assignments -

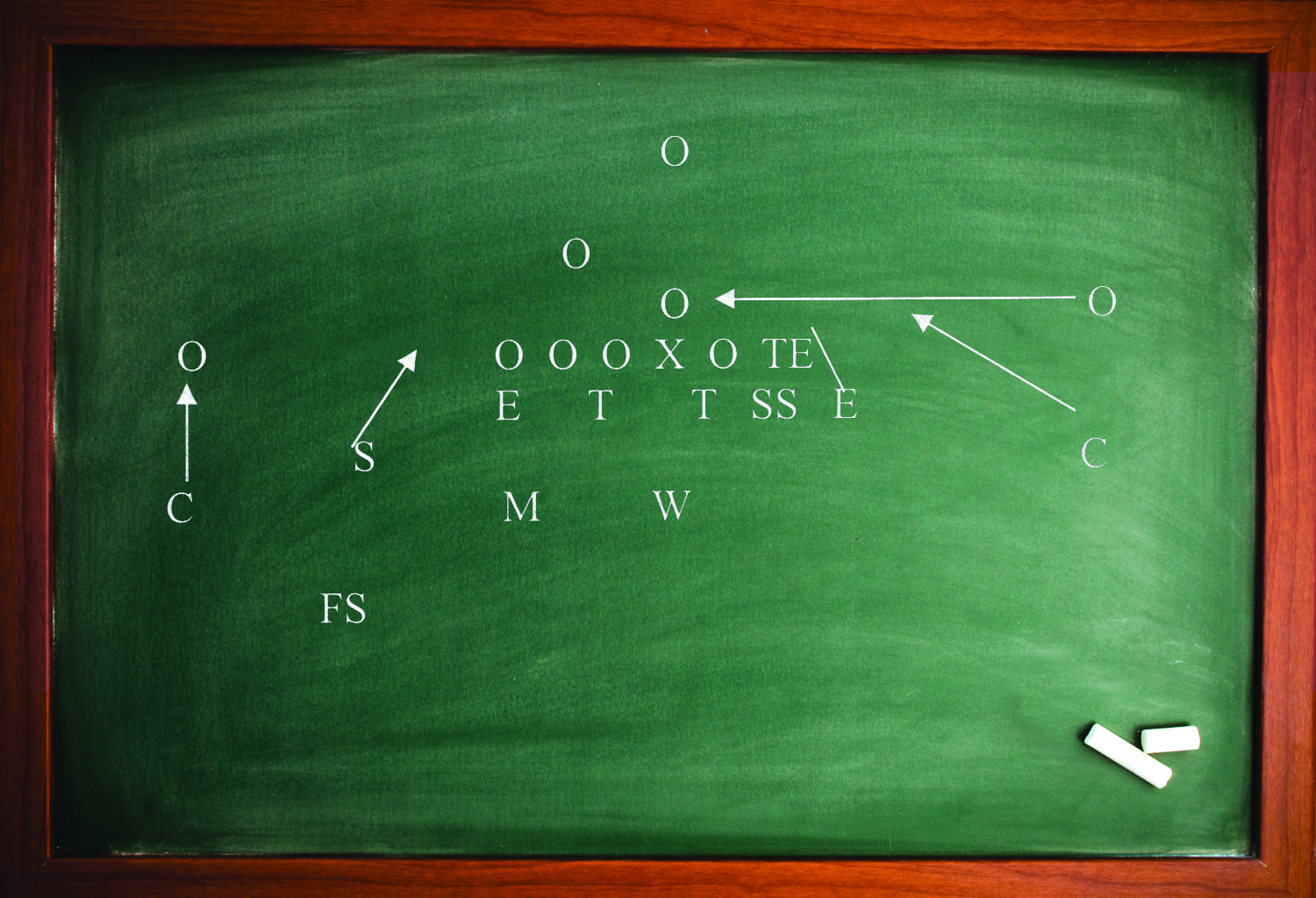

Diagram 4 Hamilton adjusted by making a defensive adjustment to the ‘joker’ check (Diagram 4). “From that point forward, we would check ‘joker’, then the strong safety would play on the line of scrimmage on the inside shade on the tight end with man-to-man technique,” said Reynolds. “The backside defensive end adjusted to a wide 5 technique and switched his gap responsibility to a weak C gap with the backside cornerback still contain blitzing.” When the opposition came back with the counter to the weak side, they still had the kick out block on the corner but the second puller then had to block Hamilton’s defensive end which left the whip linebacker in the hole to make the play. “By changing only two players’ alignments and one player’s responsibility, we had shut down the counter game and still remained sound on the front-side” said Reynolds. |

|

| HOME |

MAGAZINE |

SUBSCRIBE | ONLINE COLUMNISTS | COACHING VIDEOS |

Copyright 2026, AmericanFootballMonthly.com

All Rights Reserved